TITANICa

Discover the early development of Titanic and her sister ships, from her design and build by local shipyard workers to her launch in 1912.

Harland & Wolff: The Beginning

In 1853 Hickson & Co was established as the first iron shipbuilders yard on Queen’s Island. At the age of 23, Edward Harland was employed as the yard manager.

Such was his drive and ambition that five years later he bought the yard with the support of G.C Schwabe, a friend of his from Liverpool and the uncle of Gustav Wolff. Wolff had been working as Harland’s private assistant and in 1861 the Harland & Wolff partnership was established.

Sir Edward Harland died on Christmas Eve in 1895 and many paid tribute to the contribution he had made to the success of shipbuilding in Belfast. The following year William J. Pirrie took over as chairman and a new phase in the development of the industry began.

Tools of the Trade

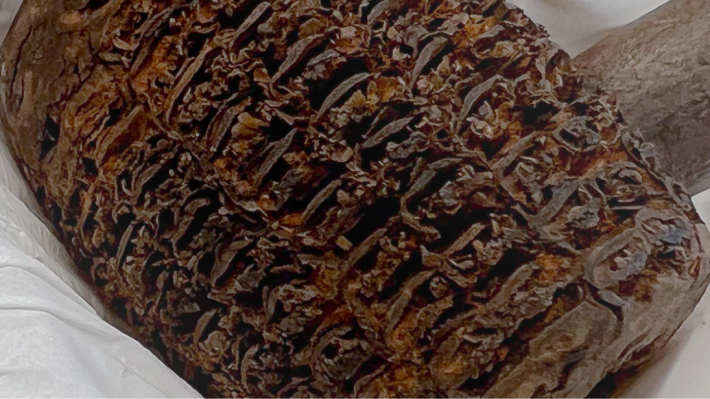

Workers used their own tools in the shipyard. This tool chest was owned by a Harland & Wolff shipwright who built lifeboats. It contains a caulking mallet and various caulking irons, used to drive fibres into the seams in wooden boats to make them watertight.

Here you can see a set of Harland & Wolff timekeeping boards. These were used by shipyard workers to ‘clock in and out’ and enabled the correct wages to be calculated for each day’s work. The scale of the company meant organisation was essential. For example, when Titanic was under construction around 15,000 people were employed at Harland & Wolff.

Exceptional Workmanship

The chair, from the Second Class dining saloon on Olympic, is identical to ones that were on board Titanic. It is made from mahogany, carved in the Art Nouveau style and mounted on a cast iron base, which was screwed to the floor. The inset seat has been re-upholstered, however, the original furnishing would have been made by skilled women in workshops within Harland & Wolff.

This carved oak panel comes from a newel post on the Grand Staircase of Olympic, one of Titanic’s sister ships. The beautiful design and craftsmanship was inspired by the work of seventeenth century master carver Grinling Gibbons (1648–1721). An identical panel, now in the Maritime Museum of the Atlantic, in Nova Scotia, Canada, was retrieved from the water after Titanic sank.

Transatlantic Emigration

Emigration was the driving force behind the growth in demand for ocean transport in the late 1800s and early 1900s. Millions of people left Europe to seek new lives in America and transporting them across the Atlantic became an increasingly important business.

This c. 1880 map illustrates how the many steamship companies were operating on Atlantic routes. The White Star Line (the company that owned Titanic) had to compete against its rivals to attract passengers. An average of nearly 900,000 immigrants entered the United States each year between 1900 and 1914.

One-way Ticket to America

This is a White Star Line ticket receipt for a sailing from Queenstown to New York in 1879. The passengers are listed as Patrick and Catherine Foley and their children James and Mary. The young family were accompanied on their journey by Michael Murphy, although it was John Murphy who bought the ticket. The steerage was prepaid and for the three adults and two children cost $112 – that’s about $2600 (£1620) in today’s money.

The White Star Line helped emigrants with promotions such as special rates and through tickets to final destinations. Many emigrants entered the United States through the Ellis Island Immigration Station in New York.

Life on Board

This china pattern, known as English Rose, was specially designed for exclusive use in the restaurants on Olympic and Titanic. The interlocking green letters ‘OSNC’ stand for Oceanic Steam Navigation Company, the official title of the White Star Line. Afternoon tea was served from 4.00pm to 5.30pm in the restaurant and cost 2 shillings per person. A la carte restaurants were provided on Olympic Class ships and First Class passengers paid extra for this exclusive dining experience in beautiful, elegant surroundings. The à la carte restaurants were operated as private franchises, but remained under the White Star Line’s overall management.

First Class Dining

This First Class silver plated fruit dish and grape scissors were designed and manufactured in 1909 by Elkington & Company, Birmingham. The same can be said for most of the silver-plated tableware used by White Star Line between 1871 and 1934.

The range of china and tableware in the exhibition can be seen to reflect the social hierarchy of the time. Not only did First, Second and Third Class passengers have specific sleeping, dining and public areas, but the items provided for their use were all designed according to where they were to be used on board. For passengers, this division simply mirrored everyday life on land.

Individual Requirements

The White Star Line catered for special categories of passengers, such as members of the Jewish faith who required Kosher food. In 1912 many Jewish emigrants to America came from central and eastern Europe.

China and silver-plated tableware was specially marked with either the words ‘Meat’ or ‘Milk’ in Yiddish and the food and tableware were prepared and washed in a separate part of the kitchen.

The servants and crew also had their own tableware specially marked for the officers’ or engineers’ mess. Often the worn or damaged silverware from First and Second Class was marked and reused in this way.

Duty and Responsibility

The White Star Line prided itself on the high level of service that it provided to its passengers. Stewards and stewardesses were assigned to serve First, Second and Third Class travellers, making sure that their journey was as pleasant as possible. The captain and his officers were in charge of operations on board ship.

Captain Edward J. Smith was in charge of Titanic the night it sank. He ordered the lifeboats to be filled with women and children. There were not enough lifeboats for everyone and many were not filled to capacity. When Titanic sank at 2.20 am on 15 April, over 1,500 lives were lost, including that of Captain Smith.

Survival and Loss

Rosa Abbott was a Third Class passenger on Titanic, travelling with her sons Rossmore, aged 16 and Eugene, aged 13.

The family ended up in the water when the ship sank and Rosa Abbott was pulled into collapsible lifeboat A. She was the only female passenger to be rescued from the water. She later transferred to collapsible lifeboat B, but suffered leg injuries from the cold water. Her sons did not survive.

The reverse of this photograph is inscribed ‘To dear Mrs. Lessman, in remembrance of the S.S. Titanic. April 15th 1912 Rosa Abbott, Survivor.’ Mrs Lessman was a passenger on board Carpathia when it rescued Titanic survivors.

Acts of Remembrance

Many different memorials have been created to those who died in the Titanic disaster. Those dedicated to named individuals are perhaps the most poignant and recall the very real sense of loss experienced by those who knew them.

This cello back plate pays tribute to the cellists on Titanic. The reverse documents their names and addresses, records that they were employed by C.W. & F.N. Black of Liverpool and refers to the memorial concert in London on 24 May 1912. All eight of the musicians on Titanic died in the disaster. They were reported to have played ‘Nearer, My God, to Thee’ as the ship sank.

Public in Mourning

Postcards were very popular in the Edwardian period. They were a cheap and easy way for people to communicate with each other at a time when telephone use was not widespread.

This is one of a series of postcards featuring symbols and inspirational text that are typical of this era. The images reflect the sense of loss and mourning after the Titanic disaster. Such cards were widely published and proved very collectable both at the time and more recently.

‘A Night to Remember’

The dramatic story of Titanic has been interpreted many times on screen. The iconic 1958 film ‘A Night to Remember’ was an adaptation of Walter Lord’s 1955 book. Lord had interviewed sixty-three Titanic survivors and both book and film were praised for their accuracy. The film was produced by Belfast-born William MacQuitty. At the age of six, his father had brought him to watch the launch of Titanic and he later recalled his emotion and pride in seeing the huge ship enter the water. His personal connection with Titanic fuelled his enthusiasm for the notable film which he produced over forty years later.

The film opened on 3 July 1958 at the Odeon Cinema, Leicester Square, London. Several Titanic survivors attended the event.